For the past few years, school districts across America have been faced with an ever-growing push to ban books from their libraries and classrooms. Advocates for these book bans say it is to protect children from harmful content, but others believe these bans do the opposite—that they inhibit the children and their ability to learn.

This rise in book banning comes during an age of increased diversity not just on the shelves but behind the keyboard too. Books, especially for children and young adults, are getting more diverse, telling and sharing unique stories and experiences from marginalized groups. This sudden push to keep these books off the classroom shelves is being called into question.

According to PEN America, there were 3,362 cases of book bans across the 2022-2023 school year. This is 33 percent higher than the previous school year, which had about 2,532 cases. This school year alone, there have been 1,557 titles banned, making a total of 2,823 titles since PEN America began gathering data in 2021.

But what is considered a book ban? It’s important to note that book bans primarily take place in a school setting. If a book is restricted in a school library or classroom, whether it be temporarily or permanently, then it’s considered “banned” by PEN America. The organization separates the types of book banning into four classifications: “banned pending investigation,” “banned from libraries and classrooms,” “banned from libraries” and “banned from classrooms.”

The majority of recorded book bans this school year, 44 percent, fall under “banned pending investigation,” meaning they’re pulled off shelves and their content is reviewed. These books have either been checked and returned to the library or still await review. Even if they are returned, there are many instances where reviews take multiple months, keeping these titles away from students.

Of the recorded book bans this school year, 38 percent of them fall under “banned from classrooms and libraries,” with 1,263 instances of a complete book ban from a school library and individual classrooms. This is a dramatic increase from the 333 instances in the previous school year.

These book bans are born from a variety of factors, and most of them are pushed by public pressure from national advocacy groups or individuals affiliated with those groups. This, paired with bills passed in state legislatures such as the "Don't Say Gay" bills in Florida, which banned or restricted discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity in specific grade levels, led to the sudden spike of book bans we see today. PEN America calls this fight against books the “Ed Scare,” where fear of public education pushes people to advocate for the restriction of certain topics from school discussions. Most of these topics include race, sexuality and gender.

It’s not surprising that many of the books targeted by these bans include characters of color or discussions of race and queer themes. PEN America also found that books that focus on or mention physical abuse, health and well-being, and death have also become primary targets this year, a push they attribute to the extensive outcry of “age inappropriate" content in schools.

According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, of the 3,451 published books the organization received this year, 40 percent had at least one creator of color, and 46 percent had meaningful representation of characters of color or included real-world events focused on different cultures and backgrounds. Additionally, 39 percent of the reviewed material had a main character of color or a nonfiction work revolving around a person of color.

The number of books reviewed by the CCBC is about the same as the number of book ban cases this 2022-2023 academic year. Of the books banned, 30 percent of them included characters of color or discuss race and racism, and another 30 percent included queer characters and themes.

These bans are acting under the guise of helping children when in reality they only harm them. Books, both fictional and nonfictional, are learning tools for people of all ages—they take us into a world different from our own, introduce us to people different from ourselves and show us problems we’ve never had to experience. It gives a new perspective, and taking away that perspective only leaves a person unaware. Sharing diverse stories allows different people to understand one another, to explore other possibilities. Restricting these stories from public schools is the complete opposite of what they’re meant for.

There has been a lot of public outcry regarding this recent push for banned books. In September 2023, Scholastic announced a plan that would help schools subjected to book bans by putting books relating to race, sexuality and gender in a separate collection called “Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice." This way, schools could decide whether or not to order that specific display. The publishing firm immediately received backlash for their decision; National Public Radio cited a post by Amanda Gorman, a poet whose book was also put in the collection. Those against the plan argue that these books are necessary now more than ever—separating and isolating the voices of marginalized groups does more harm than good.

On February 12, 2024, the State Board of Education approved of regulation 43-170, which gave the board control over book reviews in South Carolina schools. Rosie Booker, a Senior at USC and a member of the school's American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) chapter attended the board meeting against the implementation of the amendment.

"Primarily," Booker started, "we were there to raise awareness on this side of the teachers and librarians that we believe that they have the agency to design what books are appropriate for children." The ACLU also wanted to remind the school board of the recent nationwide push to ban books and educational material from school systems, especially books that focus on more diverse identities and content.

"These book bans aren't existing in a bubble or for any real moral judgment," Booker stated. "It's simply to silence kind of minority voices."

Booker mentioned how a lot of the conversation during the hearing revolved around what's considered "Age and Developmentally Appropriate" according to the board and to concerned community members. Booker believes this fear of explicit content in schools will be abused by those pushing for these book bans, and she details a specific example from the hearing. An anti-regulation speaker brought a book on the ban list in front the board and read it in its entirety--it was completely kid-friendly and was only marked explicit due to a reference to same-sex couples.

"This is largely due to, like, a greater issue that's kind of happening in the courts right now," Booker explained, "that they're trying to sexualize the existence of gay people." Booker goes on to explain how this push to sexualize queer relationships is the reason why any media featuring a queer person may be labeled as age inappropriate and explicit.

Booker believes that due to this fearmongering, middle schoolers and high schoolers will be affected the most. She discusses some of the books being banned under "Age and Developmentally Appropriate" where abuse and rape have literary relevance. In books with literary merit, these themes have a purpose, one meant to teach a lesson or share a story. Booker explains how a lack of exposure to these topics in literature could lead to students being unaware if they're experiencing them in real-life.

Diversity Awareness Youth Literary Association, an organization of teachers, students, and librarians in South Carolina, also attended the hearing, and many of the high school students gave testimonies against the regulation. Booker remembered how many of them specifically discussed abuse and how literature is used to save people from dangerous situations. "One of the students was like, 'How can we allow children to experience this kind of violence at home and not be able to read about it?' And I thought that was just so impactful."

Booker also highlighted how Gen Z is the generation with the lowest teen pregnancy and teenage intimacy rate thanks to major pushes for sex education. Now that we're starting to draw back on these resources, there's bound to be consequences.

But the key word in this discussion surrounding sexually explicit material is "children," one that was thrown around constantly during the hearing. Booker emphasized how there's no books with depictions of sex in elementary school libraries or a puberty book in a kindergarten classroom. But when people put the word "children" and "sexually explicit" in the same sentence, it will cause an uproar. "I think that's a really purposeful hyperbolism of what's actually happening to discredit librarians and teachers," Booker explained, "and kind of make them seem like they don't know what they're doing or that they have a purposeful agenda to taint the youth, basically."

But this push to ban books is not just about explicit content, it's also an attack on diverse voices. Booker explained how a lot of the meeting was dominated by what's considered age inappropriate, and how people glossed over how many books on racial injustice were at risk. South Carolina has a rich, diverse population, and it's important that this is reflected in the literature its schools teach. "I think trying to erase that history," Booker said, "and hiding those books about minority identities and covering up that whole aspect of it is so dangerous."

That's not to say all parts of the regulation were cause for concern. During the hearing, a few amendments were added to the fourth clause of the regulation, stating that only parents and legal guardians can file for a book to be reviewed, and they can only submit five complaints each calendar month. Before this added amendment, there wasn't a rule stating who can and cannot file a book complaint. This allowed one woman to submit 572 books for review in Dorchester School District 2 in South Carolina. Due to the broadness of the former guidelines, she was able to submit these complaints even though she did not have a child who attended school in that district. Additionally, only 160 books were actually present in the school district. So far, this has been the state's largest mass book ban attempt.

Parents play a vital role in school systems. It's important that their voices aren't drowned out by those from the outside. "I think that there is nothing wrong with parents and guardians having an active say in what books that are at their children's disposal," Booker explained. "I think that parents trust these districts a lot more than these outside entities who are actually pushing an agenda."

The board also added another amendment: a book that's filed for complaint does not automatically go to the board. Instead, the parent would have to meet with either the teacher or a representative from the district where the book is available. Booker believes this method is an improvement from the book's fate being solely in the hands of the school board. "Teachers and librarians know what they're doing," Booker stated. "They know what's appropriate for children."

While there are some good amendments added to the regulation, it doesn't tackle the root problem. This regulation--and many others like it nationwide--is a result of a massive push to keep students from having access to more diverse and eye-opening material. This isn't an issue that can be ignored, not when it's finding its way into our courts and legislation.

With this influx of restricted literature both nation and state-wide, some professors at USC are bringing the discussion to their classrooms. Such is the case with Anne-Laurie Sabathier, a PhD student and graduate teaching assistant in the English department at USC. Sabathier teaches a Capstone introductory English course focusing on queer literature. She decided to teach banned books in her class, hoping that her students could make their own opinions on why they were banned rather than a state legislature doing it for them. Sabathier explained the importance of uplifting these banned books where they’re accessible.

Discussing these books is only one step forward in the fight against book bans; it also takes some personal reflection and self-evaluation. People need to think about why books are banned, what factors come into play and whether or not the ban is justified. That’s the whole reason why Sabathier teaches these banned books in the first place—to make her students think for themselves. But people must also question their own selves and pick out what preconceived beliefs, such as religion or political ideologies, could make a person biased.

“Books are banned for a reason,” Sabathier said, “and those bans can be contradicted. The fact that those bans do not exist in all states and in all countries does say something about that.” Sabathier also highlights the importance of listening to both sides so her students can form their own opinions on these banned books.

There’s a reason Scholastic thought putting the more diverse stories in their own collection would help schools better navigate the bans in their area—it’s because books like those are the ones being targeted.

“I do think that the more diverse we get, the better it is in terms of representation,” Sabathier said, “but also it is going to feed into debates of banning books.”

The more book bans increase, the more they’ll affect both school systems and the writing industry. It’s currently hitting student education the hardest, though it’s still too early to see their full effects.

Sabathier believes restrictions on these books will ultimately keep students from having a more well-rounded and understanding learning experience, stating: “Because, no matter if you agree with things or not, knowing that they exist and foreseeing that differences exist will make you a more open-minded person and will play on how you accept people and be a good human in society.” Restricting different perspectives will only perpetuate ignorance, and students may miss a vital part of their education.

School librarians are also pushed between a rock and a hard place. Sabathier states that most librarians are against these book bans, but there’s not much they can do without potentially losing their jobs.

“It is a tight battle to fight, especially if you consider job security, and then your own activism as a person and what you deem to be worthy of being on shelves or not,” Sabathier said.

While the voices of these writers are being silenced in schools across the country, they’re still accessible outside of the classroom. These banned books are still being sold in different bookstores throughout the country, sometimes getting their own displays. Sabathier reminds us that there will always be independent publishers, so even if larger publishing firms do get wary of their works potentially being banned, there will always be a way to get the kinds of books being targeted on the shelves.

“All the books that have been now banned have been published in the past,” Sabathier said, “so that does mean that some people do want to publish them.”

Diversity in literature matters—it gives a voice to marginalized groups that have historically been silenced, and it allows readers from those same groups to see a reflection of themselves on the page. Taking those opportunities away from children does more harm than good. It makes these kids feel ostracized, like they're not as special or important as someone who looks or loves or feels differently. Children from all backgrounds should be able to pick up a book and see themselves staring back at them.

That isn’t to say all representation is perfect. There are still clear biases toward white creators and stories, with 71 percent of the books reviewed by the CCDC having at least one white creator. While white, straight and/or cis writers create characters from marginalized groups they don't belong to, sometimes these groups are misrepresented or are given harmful stereotypes.

Sabathier touches on this subject in class, asking their students, “Is all representation good representation?” Sabathier believes that the group being represented should have a say—that they can decide if they have been represented correctly.

“If you have an informed background or identify with what's being presented, you should have a say in the debate,” Sabathier said. “You should have a seat at the table.” Adding diverse characters in a novel and then not listening to the identity you wish to represent is a disservice; it calls your authenticity and intent into question. It’s important to share their experiences and ensure the representation they're receiving isn't harmful.

This unlocks another debate: Should straight authors write queer characters? Should white authors write characters of color? These are the kinds of questions Sabathier asks her students. She explained how her students answered differently for both. Most said yes to the first question while answers weren’t as definite for the next. For Sabathier, the answer lies with research and intent.

“But the main answer that came out of this debate was how you should be well-versed in what you're writing and what you're describing,” Sabathier said. She goes on to say how creators need consultants, someone rereading manuscripts or any person a part of the community they wish to represent checking their work. Accurate representation is true representation.

Playing into stereotypes sets a dangerous precedent—it wrongfully paints a marginalized group in a harmful light, leading to the formation of prejudiced and bigoted thoughts and ideas. There's a reason books discussing sexuality and gender are being banned, and there's a reason books on race and racism are being banned as well. Those who advocate for these book bans tend to hold their own bigoted biases, those of which drive their need to censor marginalized stories, especially ones that deal with sensitive topics in history. This censorship eventually uplifts the twisted or inaccurate portrayals of those marginalized groups created by white, cishet authors.

The American Library Association lists three typical talking points used to challenge and ban books: that these materials contain "sexually explicit" content, "offensive language" or that it's "unsuited for any age group." While these reasons are seemingly righteous, they're used to target more personal qualms, usually aiming for books discussing marginalized identities.

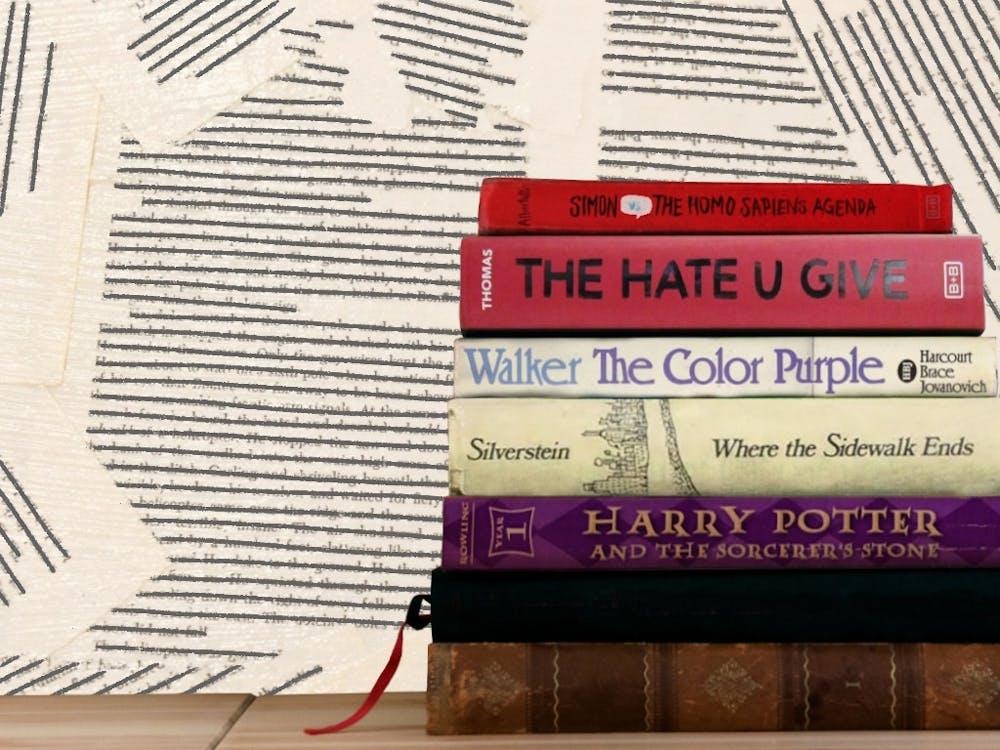

Labeling any talk of sexuality or gender as "sexually explicit" or something inappropriate for children is the cause of a personal bias and restricts kids from broadening their horizons. One book could open up an entirely different world, one they may not have realized they're a part of. The same goes for books discussing race or racism—the sudden call against critical race theory has led to books like "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas being banned or challenged in certain districts. Some of these instances have little to do with critical race theory, but some groups consider the content "inappropriate" or "indoctrinating." It's important to counter this dangerous rhetoric and keep these important and diverse books in school libraries.

While bookshelves get more diverse, more hands are racing to keep them off the shelves. It's important now more than ever to share and uplift these stories; censorship must not become the norm. Children should be seeing more and more books flow into the classroom. They should not be barred from learning, from seeking more knowledge.

Books are meant to be rich with diversity—they're meant to show us different perspectives, experiences and histories. Limiting the voices that have historically been silenced is not teaching students anything but hate. Empty shelves help no one.