Cannabis sativa. Two controversial words that carry a heavy connotation. Enter: industrial hemp, a misunderstood plant often quickly associated with its psychedelic look-alike, marijuana.

In 2018, the South Carolina Department of Agriculture launched the Industrial Hemp Pilot Program. Twenty farmers were granted permits to grow up to 20 acres of industrial hemp – the first time the plant has been legally grown in the state since World War II.

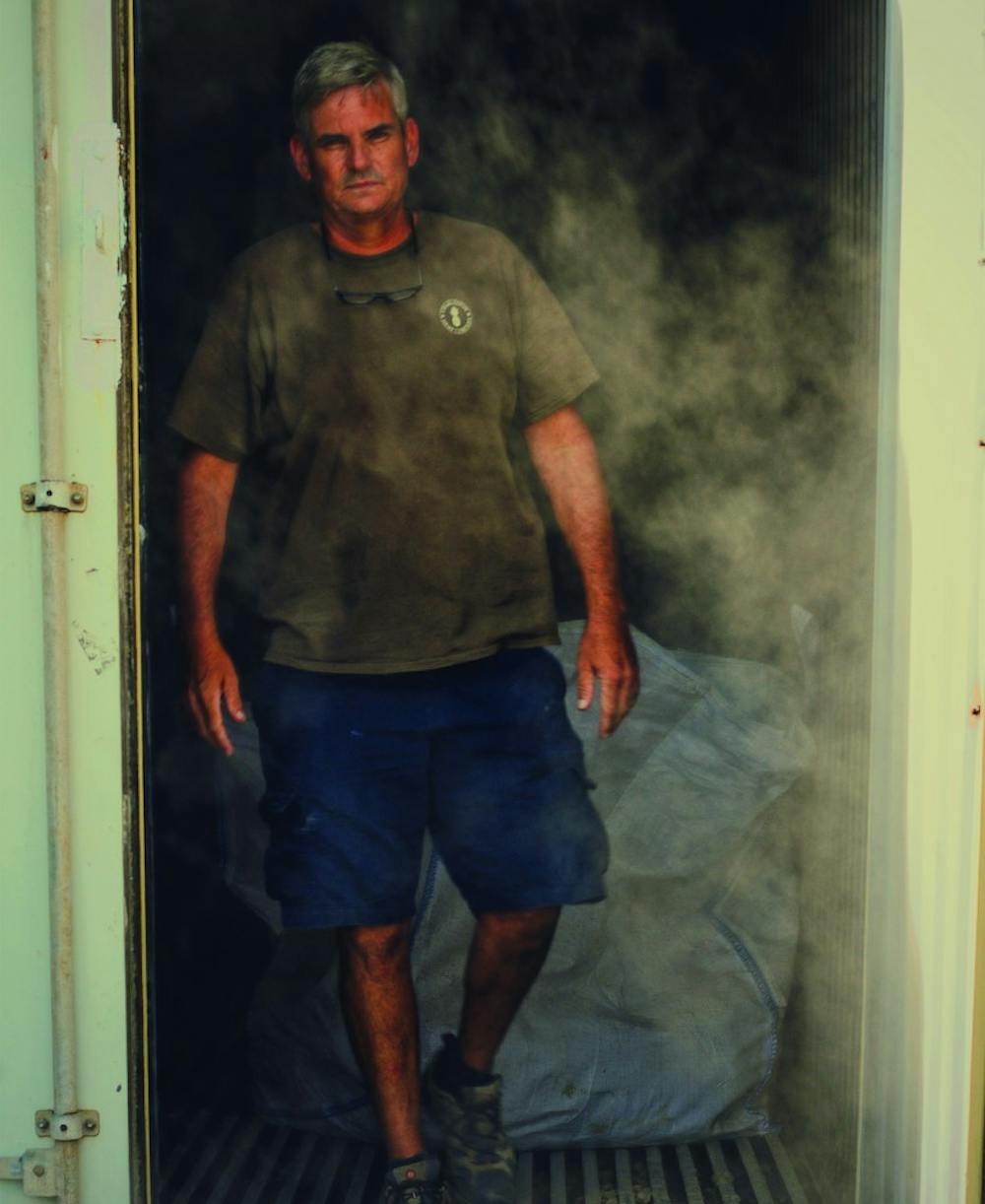

David Bulick was one of the 20 farmers selected.

“A lot of people don’t know you can’t get high from it. They just see weed ... I could give you a 20-pound bag and rolling papers, and you couldn’t get high," Bulick said.

David Bulick steps out of an industrial freezer.

Cannabis is a plant family that consists of two main strains: indica and sativa. Hemp is of the sativa variety. Cannabis contains different chemical compounds, known as cannabinoids, that affect the body in different ways. Two major cannabinoids found in cannabis are THC and CBD. THC has psychoactive properties that can get users high – marijuana usually has a THC concentration of 10 to 15 percent, while industrial hemp has a THC concentration no higher than 0.3 percent.

Some strains of industrial hemp have high percentages of CBD, which makes it a popular choice for medical use. Other strains are cultivated and used to make textiles, concrete, rope, clothes, food and plastic.

Derek Underwood, assistant commissioner for consumer protection at the S.C. Agriculture Department, said even some of the faculty within the department were unsure about hemp production in the state.

“We had to change the culture of the language here because we were all very skeptical about hemp,” Underwood said. “The number one thing we had to do before we started doing the education was that everybody had to get on the same page about what this was called: Industrial hemp.”

There are distinct differences in the chemical makeup separating marijuana and hemp, as well as obvious differences in physical appearance. Marijuana plants usually are shorter and fatter than hemp plants and have lots of broad leaves. Industrial hemp is taller and skinnier, with few leaves at the base of the plant. Despite these differences, there have been multiple thefts from hemp fields in South Carolina, presumably by people that have mistaken the plant for marijuana.

“One of the farmers, they don’t go there by themselves anymore because if you have somebody that’ll go in broad daylight and pull up five or six of your plants, there’s no telling what they’ll do,” Underwood said. “Even with big signs up: ‘This is not marijuana. This is industrial hemp. There is no THC.’ But they see it and steal it.”

Bulick hasn’t experienced any theft from his property, but the nature of the industry presents new obstacles and challenges each day.

"No matter what the challenge is you just gotta find the resolve and you move onto the next ones,” Bulick said. “Everything that we do. It’s not a problem, it’s a challenge. We work through challenges and life is just that way.”

Farmers were responsible for researching all aspects of the industrial hemp growing process – everything from different planting methods to types of seeds. For Bulick and many other farmers, this resulted in a lot of trial and error.

After Bulick received his hemp permit in January, he traveled around the country to collect 175,000 hemp seeds.

For one such journey, he flew into Portland, rented a car, and drove an hour and a half into the woods with $40,000 cash. He eventually arrived at a 100,000 square foot industrial hemp farm. He met growers and selected the seeds and the strains he wanted while employees put them in vacuum sealed bags.

As he traveled back to South Carolina, these vacuum sealed bags of hemp seeds were nestled in Bulick’s luggage. Since hemp is still classified as a controlled substance, and each state’s laws are different, Bulick researched each state’s hemp regulations, printed out the legislation, and placed the documents in his luggage next to the seeds.

Bulick never encountered any problems transporting hemp seeds, but a few other farmers weren’t as lucky. Underwood said that some South Carolina hemp farmers had their seeds confiscated at post offices.

In late September, Bulick and his team harvested 41,000 hemp plants from two super greenhouses in Awendaw, South Carolina. He is also the owner of Charleston Hemp Company, which produces a range of CBD products like oils, disposable vaping pens, salves and lip balms. By mid to late November, Bulick plans to have a new line with over 70 CBD products implemented, including everything from bug spray and massage oil to edible gummies and bath bombs.

Bulick is also one of only two industrial hemp processors in South Carolina. According to Vanessa Elsalah, agriculture outreach specialist and industrial hemp coordinator, Bulick stepped up and became a processor after there was an obvious need in the state. The hemp used to create Charleston Hemp Company’s products are processed at Bulick’s site in Ridgeville, meaning that the products are “seed to shelf local.”

The farm bill mandates that all industrial hemp production is coupled with a research component. Five universities statewide partnered with the 20 hemp pilot farmers. According to Elsalah, the research component serves as a way to further explore the potential uses of hemp.

“We wanted to prove that this crop could be used for many, many different things – not just CBD oil, hemp oil or fiber,” Elsalah said.

Underwood emphasized the importance of hemp research while the program is in its infancy – noting that according to some sources, each acre of hemp can costs thousands of dollars to produce. Currently, there are no pesticides approved for hemp farming, meaning that most of the hemp produced in the state is done so organically. This makes the plant more susceptible to insect infestations that could destroy a field.

In addition to conducting industrial hemp research, Bulick has partnered with the Medical University of South Carolina to launch an accredited college course that teaches students the hemp growing process. The program should be implemented in time for the spring 2019 semester. He sees this teaching facility as a way to further educate communities about hemp and its uses, and by starting with college students, he hopes that the information will eventually make more people comfortable with the idea of hemp.

Bulick foresees a future South Carolina at the forefront of the CBD product industry, where people from across the country could travel to the state to learn the process.

In October, the state agriculture department announced the second round of selected hemp growers – this time, the list now includes 40 growers who are allocated 40 acres each. Underwood hopes by the third year of the program, it will eventually expand to allow for unlimited growers with unlimited acreage.

Despite the misconceptions surrounding hemp, the industrial hemp pilot program has the potential to redefine hemp as a medical and industrial tool – and it’s the pioneer hemp farmers that are making it happen.

For them, there is no set of standards. There is no guidebook.

“Every day is a freaking circus. It is great,” Bulick said. “That’s life.”