“It’ll be much easier than what you’re used to,” they said. “But you’ll constantly have homework, and you’ll be graded on attendance and class participation.”

These are the words of wisdom I received from the University of Leeds before I departed for my year studying abroad in South Carolina.

Since being here for six weeks, I’ve found most of the advice is accurate. Studying at USC is a different story altogether—embracing a paternalistic style of education that is typical of American university life as a whole.

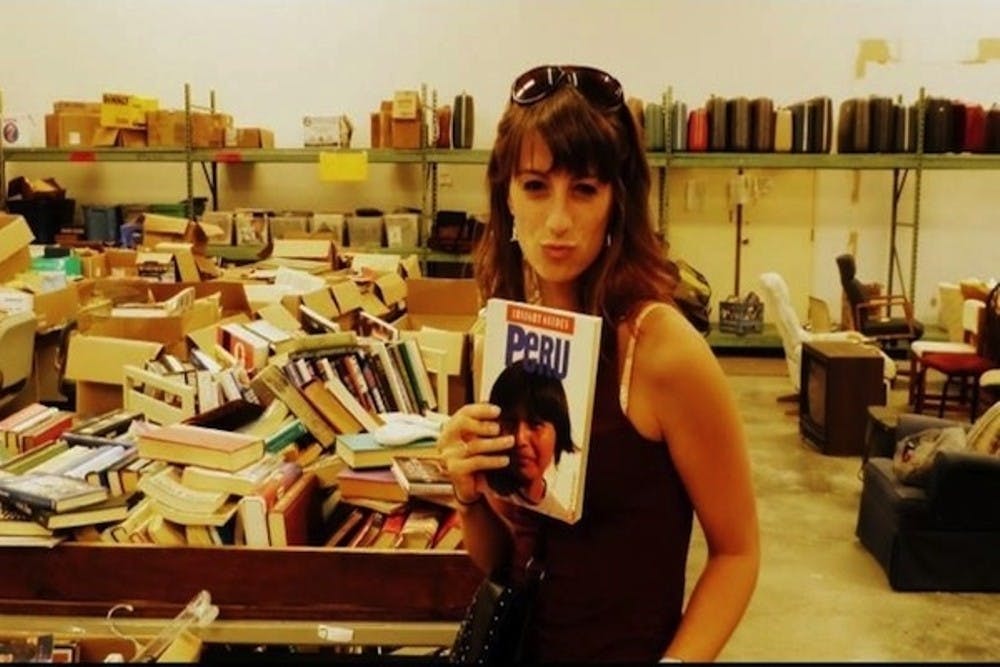

Having studied at USC for some time now, it has become apparent that, in comparison to the way things are done back at home, the American education system assumes that students lack initiative. It assumes that we won’t contribute in class, (if we even turn up) that we can’t fathom borrowing books from the library, and that we can’t revise rough drafts by ourselves. So “lively, informed and consistent” class participation is included in part of our overall grade, as is attendance. We have to buy or rent all of our books from the university’s bookstore—I spent a whopping $250. We are given staggered deadlines for essays, in which the “rough draft” is due, and two weeks later, the final draft is due. In between these dates, we have to co-edit drafts with two of our classmates.

Along with the infamous U.S. drinking laws, what seems inevitable here is that turning 18 and going to university in America doesn’t necessarily mean you become an adult. You may be of adult age, but moving out and going to university is as if you’re an ornament wrapped in bubble wrap, getting transferred from one cardboard box to another. Rather than lowering the barriers to independence, the U.S. education system keeps them firmly in place at university. From the perspective of a British exchange student, I can say with confidence that going to university in the U.S. feels more like going back to high school.

Thinking back to when I started university in the U.K., I remember feeling as though I’d been plunged in at the deep end. No longer did we have “classes” like the U.S., but teaching is divided into huge lectures and small seminars, which creates a zoom-in effect, looking at the broader picture and then cultivating responses to it. If we fail to attend lectures and seminars, we receive intimidating emails from department staff, but other than that, if you choose to stay in bed and be hungover all day, that’s your funeral. Final exams and coursework can count for up to 100 percent of our module marks, rather than small pieces of homework set throughout the semester. Only one or two set texts are mandatory, as all others can be found and rented in the libraries.

The U.K. trusts that students have initiative and drive. The U.S. assumes this drive for us.

One of the differences I’ve found the most surprising is the USC English department’s guidelines for writing a thesis. At Leeds, our thesis is the same as our title at the top of the page. For example, a poetry essay at Leeds might be titled, “Examine the Ways in Which Edgar Allan Poe Draws Upon Themes of Mental and Physical Confinement.” At USC, however, our title must resemble a dramatic and innovative newspaper headline, like “Polarities Enchained” or “Locked in the Brain.” The first paragraph is then a statement of intent, with the thesis statement acting as the last sentence. It took a good ten minutes after class for me to clarify that this really was what my tutor was after. It turns out that writing essays in the U.S. allows for much more creativity and personal touches than in the U.K.

There are a number of other perks to this puzzling chasm between the U.K. and the U.S. In the U.S., students are allowed to create their own timetables: I made sure all my classes were on Mondays to Thursdays so I’d have long weekends available to travel (and blog, of course). Getting free reign over assignment titles is also pretty cool, as it means we can write about what we’re passionate about rather than slogging out an essay under the guise of a pre-assigned thesis.

I’m warming to the differences in educational styles pretty well so far. After all, being open to change is part of the study abroad experience. But I think I’ll always prefer the way things are done at home. The content and assessment styles may be harder, but at least when you succeed in the U.K. you know it’s the result of your own hard work and initiative, rather than the work of paternalistic discipline.

Photo credit: Evelyn Robinson