It is easy to think that we are immune. It is easy to believe that social networks and mass media culture do not impact our worldviews and certainly not our behavior. But, we know that this is not the case.

We are social human beings who learn from watching and listening to others. Since our public sphere has moved onto the world-wide web, ideas can now spread and be shared on an enormous scale at a seemingly instantaneous rate.

In many ways, this can be positive; we can have massive conversations and consequentially speed-up social change. However, it also means that safe, thorough, verified, information often becomes misconstrued as it filters through innumerable communities online and in real life. Could our affection for humorous, sensational and salacious content be responsible for dangerous cultural shifts?

Particularly when dealing with issues surrounding feminism and women’s empowerment, this digital public sphere can be incredibly volatile. Young people are engaging with the media with an expectedly naïve, trusting attitude at a time when they are only just beginning to form their own opinions, or maybe even seeking out rebellion.

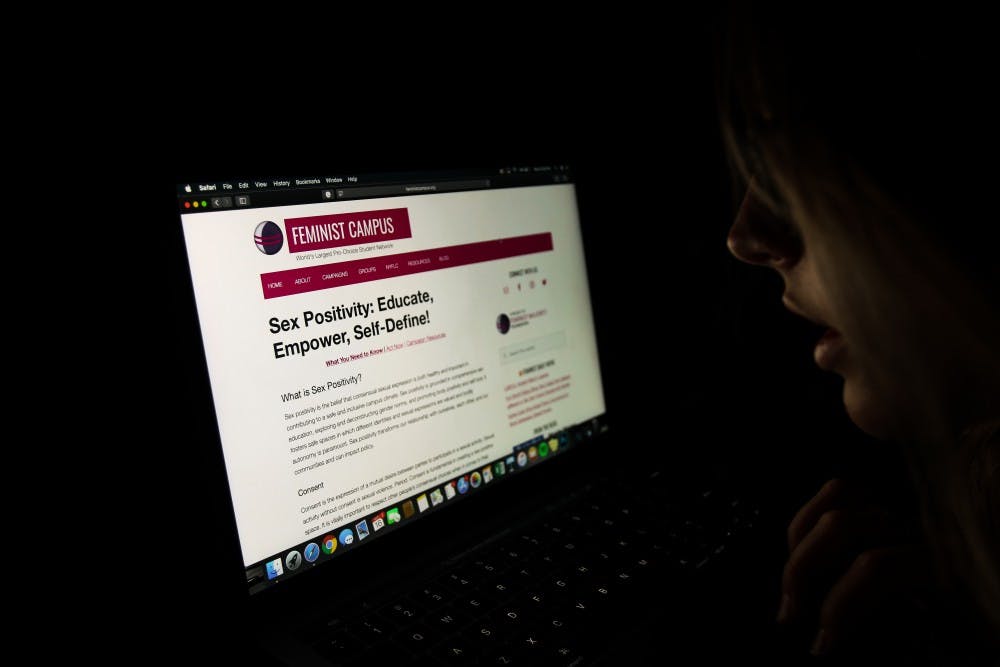

Since the beginning of third-wave feminism, “sex-positivity” has been a central issue in feminist discourse. However, as the topic of sex-positivity trickled into mainstream culture in the last 10 years, it began to take on a life of its own.

Like any “-ism,” sex-positive feminism has a simple definition and a very nuanced application. The philosophy is rooted in the idea that double standards in social expectations for men and women should be abolished for women’s liberation. It is the response to the human tradition of repressing and punishing female sexuality.

These notions of what female sexuality “should” be existed for what looks like forever. But, since the first and second wave of feminism has allowed actual female perspectives to enter the mainstream, women are finally able to air their grievances and hopefully create a world where female sexuality is not to be feared. “Sex-positive” feminism is based on the idea that women can be sexual beings in the way that men are.

It’s no secret that we live in a patriarchal society that rewards and encourages a very specific form of masculinity. One USC student said that she feels we live in a “machismo” culture, where it is a cultural norm for men to aspire to have as many sexual partners as possible. And we’ve all heard it; in school, at parties and online, men bragging about their sexual conquests or maybe even feeling pressured to lie about it to fit in. However, the same kind of behavior is considered unacceptable for women.

Our interviewee shared a common sentiment, that even if a woman is not necessarily shamed for similar behavior, it would be considered a part of her, “scandalous past.”

The answer, for a while, seemed to be the expression of sex-positive feminism. With the help of social media outlets like Twitter and Tumblr, the ideology that first emerged in the feminist discourse of the 1990s crept into the mainstream during the 2010s. Buzzwords like “slut-shaming” began to be thrown around in online and school-based communities, claiming that slurs like “slut” stigmatize female sexuality and should either be reclaimed with pride or thrown out completely. Of course, this is a positive movement for women.

But, as the nuance of opinion was squelched by mass communications, the messages that were getting to young women like myself were much flatter, cheapened. The content that garnered the most attention and shares encouraged women to seek out empowerment through casual affairs. Derogatory messages that we would consider representative of the most toxic ideas of stereotypically male sexuality were being appropriated for women, shared alongside things like advice columns for women to look their best during messy hookups or increasingly young girls posting sensual photos.

And yes, to each her own. However, we must keep in mind our social nature and how we are inclined to appropriate the dominant culture into our own lives. For many women, including one of our anonymous student interviewees, this culture, “made me think I was a prude, in terms of talking about sex, because of the patriarchy and not because I was still kind of a child.”

She said that by not wanting to have explicit conversations at 14-years-old, her peers made her feel that she was bigoted or “manipulated by society.” In the hasty application of “sex-positive” feminism, it was now wrong in many circles not to participate in over sexualizing oneself, no matter how young. Caught in the crosshairs of traditional and progressive values, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

Unsurprisingly, many women also embraced this culture. Some were influenced purely by their own desires and saved by feminist thought from traditionalist ridicule. Many, however, were responding to social pressure.

One USC student pointed out her observation that “the sex-positivity movement is sometimes warped into a promotion of unsafe acts or things women don't actually want to do in order to please men, instead of what it should be which is empowering people in their own sexuality.” Meanwhile, another interviewee shared her personal experience, stating, “I definitely feel that I was exposed to the sex-positive movement really young and it was also kind of influential on a level to hook up with people I didn’t truly want to.”

Without careful consideration, the sex-positive movement seems to betray its own aims and work as an agent of the patriarchy. This raises an essential question – how much are we really in control of?

As a sex-positive feminist, I believe that every woman, and person, is entitled to expressing their sexuality however they see fit. If that means sharing your body with everyone or with no one, that is your business, as long as it is done safely and consensually. If sexual expression to you is dressing in “revealing” clothes or posting a picture showing off your figure, then good for you. But, we need to be mindful of the kind of culture we are creating.

No decision exists in a vacuum; it emerges from and contributes to our culture. We already know that sex sells; our society is oversaturated with hypersexualized images, particularly of women. Most media portrayals of women emphasize her good looks and sex appeal above all else. So, what happens when this culture, which was once deemed derogatory, becomes the standard of feminist self-expression?

In many ways, we are living in a culture of casual kinkiness, where sex is brought into everyday elements. Even in “feminist” spaces, the male gaze becomes inescapable, as the vixen archetype takes center stage as an ideal. And this is a phenomenon among young girls in particular.

As influencer culture and approval through social media begin to amplify and typify these ideals, the subject has become an area of interest for social scientists. In 2016, New York Times’ bestseller, American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers, author Nancy Jo Sales interviews hundreds of girls across the country to learn about how this culture has impacted them. She reported on what many now-college-age girls lived through themselves. She reported that teenage girls and even some as young as 11-years-old confess that they work hard to create a sensual brand online and that that attitude has trickled into their real-life communities.

Her research found that this has become a norm or even an expectation and that most girls understand that the more sexually charged the post, the more likes and attention it would garner. Are we teaching young girls to express themselves freely or simply teaching them to fit into a new ideal image?

Dominating discussions around sex-positivity also tend to gloss over some serious related issues. One student shared a common experience, saying “I had a friend in high school who was sexually assaulted and then she started hooking up with a lot of people.” She points out that this is “one of the ways that assault survivors exhibit trauma, but stuff like that could get lost in the sex-positive movement.”

While activities we once called promiscuous need not be judged, they should not always be called organic. The discourse surrounding the potentially harmful effects of pornography has also been quelled by the sensationalized form of sex-positivity, focusing only on the expressive aspect, while ignoring the abuse and degradation of women that is rampant in the industry.

All of this discussion is not to say that free sexual expression and sex-positive feminism is bad. It is high time that the double standards and taboo surrounding sex end so that we may have an honest conversation.

But, it must be that, a conversation.

If we replace one ideal with another, we will be no better off than we were in the past. We cannot be so cavalier with our discussions surrounding sex, because the effects are certainly evident. We are creatures of the culture that we create, so we must craft our futures with care, understanding and intention.